Enjoying the View

Looking at Scenic Views as a Connection to Conservation

From sweeping mountaintop vistas to forest canopies, serene lakes to waterfalls, scenic viewpoints give us the opportunity to take a break and soak in the surrounding landscape.

More often than not, a majestic view is the key highlight to a day spent in nature, be it for a strenuous hike, a relaxing walk in the woods, or even a scenic drive. In fact, according to a 2013 study, 90% of National Park visitors rated scenic views as extremely important or very important to their experience.

Scenic views have always been an essential part of outdoor recreation—so much so that we created policies over a century ago to preserve them. When the Organic Act of 1916 was signed into law, it established the National Park Service in order to “… conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein …” The act identified view preservation as a top priority to maintain the integrity and visual splendor of the parks for future generations to enjoy. However, despite being codified into law, not all the land that comprises a scenic view is under protection.

While gazing at a natural view, it is easy to assume that what you see now will stay the same well into the future. However, many scenic views in the United States are under threat due to land use changes like new infrastructure and development. These land use changes can also impact air and water quality, wildlife, forest health, and other functions of the local ecosystem. In the face of these threats, scenic views offer a unique opportunity to connect people to landscape conservation. This piece will explore how views can inspire conservation action using two approaches: gathering data to evaluate different views and creating visualizations that deeply connect with the community.

The Visual Resource Inventory: Evaluating Views Along the Appalachian Trail

The image above shows a sweeping panorama from Signal Knob Overlook in Shenandoah National Park, Virginia. Park visitors often stop and enjoy the scenery at the midpoint of their hike. For the members and supporters of the Appalachian Trail Conservancy (ATC), this is also one of nearly 1,400 known views along the 2,193.1 mile trail that is being catalogued for a project called the Visual Resource Inventory (VRI).

As a cooperative-management system partnering with local, state, and federal organizations, the Appalachian Trail Conservancy’s mission is to protect, manage, and advocate for the Appalachian National Scenic Trail. A critical part of that mission is to protect the ecological integrity of the Appalachian Trail, which involves conserving areas that extend past the Trail’s boundaries. As Pamela Roy, the Visual Resource Inventory Manager, says, “When our visitors look at views along the Trail, they don’t see the invisible dotted line between the corridor and what’s beyond the corridor. Our foundation document indicates that we aim to preserve views beyond the corridor as well.” Beginning as a pilot program in 2019 and based on a framework built by the National Park Service (NPS), the Appalachian Trail Conservancy and partners have begun the Visual Resource Inventory process to document and assess the various views across the A.T.

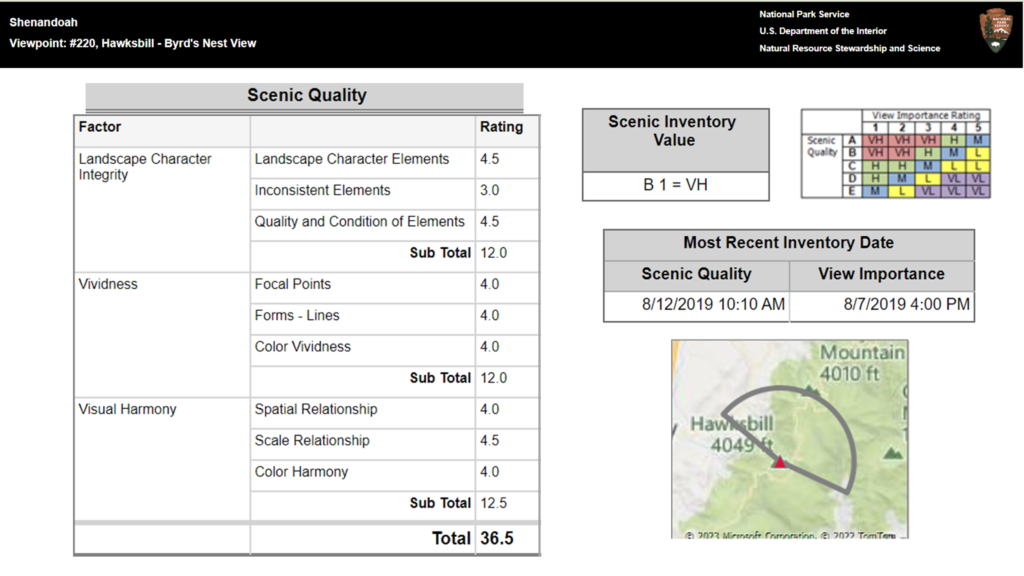

To conduct the inventory, a landscape evaluation team hikes to the viewpoint, takes photos, describes the view, records the visible features in the landscape, and evaluates its scenic quality. When combined with other evaluations along the Trail, the VRI becomes an extensive dataset that can compare different views throughout the entire length of the trail. As Katie Allen, Director of Landscape Conservation at the ATC, explains, “It provides an opportunity [for us] to look at the landscape and understand what’s within the viewshed, and make that a priority for conservation.”

The Visual Resource Inventory gives the organization a comprehensive look at the natural and visual resources within these views. Once completed, the VRI information can be shared with stakeholders to demonstrate the value of these natural landmarks, including the features that could be lost in the face of development, pollution, and other land use changes. By understanding the importance of these locations, decision makers could use this information to build credible, data-driven arguments toward preserving critical viewpoints.

Viewshed Visualizations: Combining Scientific Data and Design to Illustrate Future Scenarios

This visualization of Crozet, Virginia is based on CLI’s data and locally sourced information. The image on the left demonstrates what the view looks like in a future scenario where the region has been developed strategically, while the one on the right shows a scenario where the region is developed reactively. This view had additional local insight as David Lepage, the Nelson Byrd Woltz Graphic Designer who used image editing software to manipulate the views, is a Crozet resident himself.

Another effective method to connect views to conservation impacts is through data visualizations. Scientific research that is presented in writing can only go so far in terms of connecting research directly with communities, and abstract information like maps and graphs can have limited impacts on a wide audience. “We’re becoming so much more visual as people—reading less in depth and understanding less of what we’ve read. For better or for worse, we need to develop visual tools to communicate.” Tim Popa, Senior Associate at the Landscape Architecture firm Nelson Byrd Woltz, explains.

By presenting data visually, visualizations can elicit a visceral response from community members, and make the issue feel more relevant and compelling. The Smithsonian’s Changing Landscapes Initiative (CLI), in partnership with landscape architects and graphic designers at Nelson Byrd Woltz (NBW), created visualizations like the above example that marry landscape data with real locations in the program’s study region. Through this collaboration, the organizations aimed to create an outreach tool that communities could relate to on a direct and more personal level.

The two organizations began by selecting and photographing iconic views that would be familiar to stakeholders in the region. CLI researchers then calculated where the view could be found on maps of land use projected under multiple distinct future scenarios, and shared that information with the NBW team. The landscape architects and graphic designers at NBW then digitally manipulated the images to visually simulate the projected changes to the landscapes. To create authentic visualizations, the designers used the CLI data along with local knowledge like known regional crop types and the kind of development common to the area.

The viewsheds chosen for this project—the green hills around Crozet, the farmlands and rural homes south of Winchester, and the vista from Massanutten Mountain—represented landscapes that resonate with many people in the region as part of their home. These views also represent places of important cultural, historic, and ecological significance. By showing specific and recognizable locations, viewers might think, as Tim Popa, Senior Associate at Nelson Byrd Woltz explains, “I know that place as something I care about.”

When presented at schools, at community meetings, and to state and county planners, viewers can draw clear connections between the possible land use changes under these scenarios, and the impact on these cherished spaces. Someone might recognize a view from their favorite hike, or the roads they take through a dense forest on their daily commute. By interacting with the visualizations, viewers are confronted with the possibility of permanent changes to the landscapes near their home. Through that experience, they may be inspired to engage with efforts to protect the land.

Conclusion

ATC’s Visual Resource Inventory and CLI’s data visualizations demonstrate distinct but connected approaches that can serve as tools for conservation agencies that pursue viewshed preservation. By connecting credible data with impactful presentations, these tools have the potential to inspire and guide communities toward protecting the land that surrounds them.

But this protection is more than maintaining rewards for a hike or beautiful photo opportunities—views can also be an indicator of overall ecosystem health. Within the expansive view of a crystal-clear lake, a dense emerald-green forest, or a wide thriving meadow is a clear look at nature functioning at its best. Alternatively, views with interruptions in the natural landscape from development, deforestation, or pollution can illustrate potential threats.

This means that when conservation groups discuss view protection with the community, they can connect beautiful scenic landscapes to clean water, habitat connectivity, biodiversity, and all the elements related to ecosystem function. As ATC’s Katie Allen states, “You can make that leap from what you’re looking at to how it also functions in the landscape, and why protection is so necessary.”

The Changing Landscapes Initiative is a Smithsonian-led program that combines research with community wisdom to help secure a vibrant and healthy future for people and wildlife. CLI staff and collaborators conduct research to understand the current and future impacts of land use decisions on forest connectivity, wildlife migration and biodiversity, among other essential ecosystem services.

The Appalachian Trail Conservancy leads the effort to protect, maintain, and celebrate the Appalachian Trail. They are part of a cooperative-management system that works with local, state, and federal partners to ensure greater protections for the Trail. Their partners include the National Park Service, the U.S. Forest Service, dozens of state agencies, and 31 local Trail-maintaining clubs.

Nelson Byrd Woltz Landscape Architects applies design excellence at the intersection of ecological and cultural systems. They strive to create a culture of stewardship and engagement with the world around us for a more equitable and resilient future. Committed to design excellence, education, and conservation, the firm is engaged in a broad array of public and private projects.